Tags

Related Posts

Share This

GOING HOME – 3 of 3: ROOTS

Our roots give context to the work we do as Collaborative practitioners. Our ability to work in teams, to assist our clients, and to grow as professionals is in large part influenced by our roots.

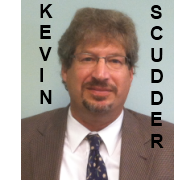

This is the third installment of a three-part report of my recent visit to my hometown of Omaha, NE. The first installment, Going Home: The Little Things, discussed the little things essential to quality Collaborative Practice. The second installment, Going Home: Inter-Practice Group Relations, focused on what can be learned from relations “between” practice groups and that it can be missed if our focus is entirely on the work we do “within” our practice groups. This installment explores our roots, what is brought to the table when we collaborate.

As you read this story, keep in mind that this is MY story. This is what I bring to the table in each of every interaction I have with my client, their spouse, and the other professionals with whom I come in contact in my Collaborative and other work. I am about values, work ethic, my lens of what is fair and just, and those experiences that have shaped who I am.

Also remember that our clients and the other professionals with whom we work come to the table with THEIR story, their history, values, faith and life experiences.

And you come to the table with YOUR story. As you read this piece I invite you to keep a paper and pen next to you so that as you read this you can note the values that guide your Collaborative work, the “why” that keeps you in the Collaborative Community and working towards being the best Collaborative Practitioner that you can be. Think about what YOU would write if you were to write about family, friends and your life experience, how your life experiences have made you into the person you are today, and how that history shapes the way you practice collaboratively. Think about YOUR roots.

FAMILY, Part 1 of 2:

In American politics Nebraska is a Red State, staunchly conservative with an economy historically based in agriculture, cattle processing, meatpacking, jobbing, railroads and manufacturing. A history of the early development of Omaha can be found in the early pages of: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/histpres/reports/omaha_south.pdf

As with many cities Omaha has its own history of civil unrest – (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_riots_and_civil_unrest_in_Omaha,_Nebraska) – and our family seemed to have a finger on the pulse of the unrest that was there during the time I lived there. The house where I grew up was very liberal (Blue). Our house was Omaha’s Eugene McCarthy campaign headquarters in 1968 and George McGovern’s headquarters in 1972. I grew up with “Impeach Nixon” mobiles over our kitchen table where we ate all of our meals.

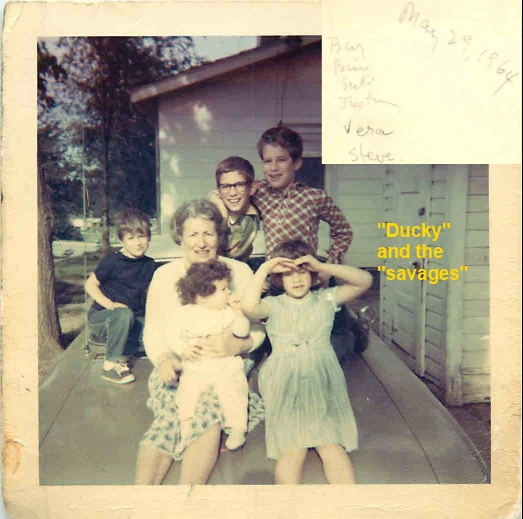

Much to my maternal grandmother’s chagrin my parents ran my family as a Democracy. Once a week we would have a family meeting over dinner and we had the opportunity to vote (one person – one vote) on important family issues, such as what we should have for dinner, should we get another pet, where we should go on our summer adventure, whether we should move. Little things like that. My Grandmother, whom we called “Ducky”, called us “savages”. Repeatedly. From the time I was five until she died in 1995 at age 98.

My grandparents on both my maternal and paternal side believed in social justice.

My mother’s grandparents lived in New York City and had a cabin in Canada. During World War II they used the cabin as a safe house for European Jews and other refugees fleeing the Holocaust when the U.S. policy was one of not accepting such refugees to this country. These refugees would stay for a while and then either be slipped into this country or given a visa so they could enter the country legally in order to live and set down roots.

My Great-grandmother, Ida Guggenheimer, was involved in many social justice issues and with social leaders of her time, including Henrietta Szold, Eleanor Roosevelt, Women’s Trade Union League, League of Women Voters, League of Women Shoppers, Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, Southern Conference for Educational welfare, Consumers Union, ACLU, Roger Baldwin (Civil Liberties Union, Margaret Sanger (birth control), and the Bail Fund for Political Prisoners.

Ida also was the patron of Ralph Ellison, financially supporting him in his writing and speaking. As a result of her support the book Invisible Man is dedicated to her. [http://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/guggenheimer-ida-espen].

On my father’s side the quest for social justice took place on several fronts.

In large part because of the railroad, being located on the Missouri River and serving as the Gateway to the West for the Gold Rush and exploration of the West, and because of the stockyards and meatpacking plants (from 1955 to 1973 Omaha was the largest livestock market in the world), Omaha is a city of immigrants and diversity.

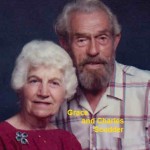

The history of the meatpacking plants is one of labor strife and the attempt of the workers to receive fair wages and better working conditions. Some of Omaha’s diversity is due to the owners bringing in different nationalities as strikebreakers. In the 1950’s both my paternal grandparents  and my parents worked at these plants and experienced the inequities there. Workers were disposable as in the post-depression and post-Dust Bowl years there was always someone looking for work.

and my parents worked at these plants and experienced the inequities there. Workers were disposable as in the post-depression and post-Dust Bowl years there was always someone looking for work.

I was raised within a sense of social justice and equality, that people should be treated like people, have a voice, and given a fair wage. This value shows up often in my collaborative cases as I support both clients as they struggle with self-worth issues and is a fertile area for showing empathy and compassion.

Shortly after my birth my father graduated from law school and after a year of working for a corporate law firm that did not fit his personality or beliefs, was the Omaha Legal Aid attorney for a number of years. Many times I would go with him to his office in the black section of town to draw pictures and watch him work. On many occasions we accepted invitations from his clients to attend church and other events where our family was the only white family. As far as I recall on all occasions we were hugged and fed and asked to join in on their singing and celebrations as if we were part of their extended families.

In the 1960’s Omaha had race riots. The Black Panthers came to town and my father represented a few of them in his work.

Opposition to the Vietnam War came to Omaha. It was a turbulent decade in which to grow up.

Through it all we sang. My parents were two of the founding members of the Omaha Folklore Society. My father still is part of the group after 50 years. Monthly the group would get together and sing union songs, ballads, anti-war songs, rounds, and children’s songs. Songs written and sung by Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger and others were a constant presence in our household.

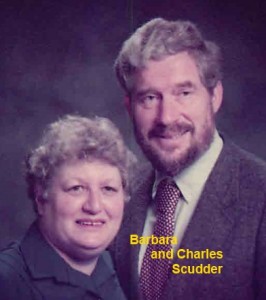

I was raised as a Jew in Omaha. We belonged to Temple Israel and my Mother waged a long battle with the Temple about annual dues. My family could not afford to pay the dues as we were a family of six children being raised in a one-wage earner household, that one job being a low-paying legal aid position.

In fact, my father was not Jewish. Some say it was a “technicality” and that he was a “practicing” Jew as he attended Temple Israel for 15 years or so when he was voted President of the Temple’s Men’s Club. To be transparent my Father mentioned that he was not really Jewish as he had never officially converted. He said later that his Presidency of the Temple Israel Men’s Club was the shortest in Temple Israel’s history as the vote was overturned shortly after my Father’s clearing the record. My father subsequently started and completed the conversion process with Rabbi Brooks but he never ran for the Presidency of the Men’s Club again.

I looked different from those around me. I was a “long-hair”. Starting in second grade, and with my parents’ consent (being the fourth of six children had its benefits) I became a free speech proponent and stopped cutting my hair, at least too much or too often. It started when my parents gave me two dollars to go to the striped pole barber at the local shopping mall. Back then it was safe in Omaha for me to go by myself while my Mother was shopping with some of my brothers and sisters.

I clutched my $2.00 and walked downstairs to the barbershop, took a chair when invited to by the barber (who had a cigarette dangling from his lips, his eyes squinting from the smoke) and proclaimed that I wanted a “trim”. My barber looked at me as if I was a person from a different planet. I already had long hair and he must have seen me as one of those “hippies” that he heard about on the news. In fact, the hippies did not make it to Omaha until about 1971, at least seven years after Woodstock and the immediate proliferation of hippies on the east and west coasts of the US; a similar delay happened with the hula hoop which did not get to Omaha until at least five years after its first sighting.

Back to the haircut:

The barber did not hesitate. With a raspy, smoker’s cackle he grabbed my bangs, yanked them up and took them off to my scalp, transforming me into a miniature Prince Valiant. Not to appear putout, and unwilling to provide this person the satisfaction, I stood up, took off the barber’s cape, handed over my $2.00 and walked out the door.

My Mother was appalled and ready to march me to the barber, give him a piece of her mind and make him clean up the mess that was now my hair. I stood in her way and insisted I was never going to return to that shop again. My Mother demurred and from there on out I was taken to a “salon” rather than a striped pole barbershop.

FRIENDS, Part 1 of 2:

While I was in Omaha I attended my 35th High School Reunion. This was the second high school reunion that I have attended, the other being my 25th Reunion.

Waiting twenty-five years to attend my first reunion gave me enough time to process the experience of having lived my first eighteen years in Omaha and to get to a place where I felt confident enough to reenter the “friend” environment in which I grew up.

The first 10 years were not bad. Having been blessed with a family that did not have many immediate financial resources much of our fun was had outdoors. Every summer we camped for a few weeks at various locations around Nebraska, South Dakota, Iowa, Minnesota and central Canada. On many weekends we would go on shorter camping trips, meeting up with other families with whom we would have many adventures involving injured pheasant, carp, mud holes, crawfish, blizzards in April and, inevitably, injured children from some mishap or other.

Elementary school (kindergarten through 6th grade) was above average. Being raised in a family that historically emphasized education I excelled academically and as a young boy I had a motor that was hard to stop, so I excelled in sports. Yes, I suffered the occasional name calling of “girl” and having my hair pulled by both strangers and people I knew, and getting punched in the groin by kids older than I to see if I was a boy or a girl. I suffered these indignities silently as I did not want to draw undue attention to myself.

Besides, I figured I had my friends and my friends accepted me as I was and had my back. These were the boys that, without having to call, I knew would be at the local playfield for a game of body-block football or baseball or keep-away or just hanging out on a field of grass watching the clouds float by. These were the boys whose homes I could go to and be welcomed by their parents and fed and sheltered as if I was their own son. They did not seem bothered that my hair was long or my clothes were a bit ragged (my having two older brothers filled out my wardrobe to a degree).

Besides, I figured I had my friends and my friends accepted me as I was and had my back. These were the boys that, without having to call, I knew would be at the local playfield for a game of body-block football or baseball or keep-away or just hanging out on a field of grass watching the clouds float by. These were the boys whose homes I could go to and be welcomed by their parents and fed and sheltered as if I was their own son. They did not seem bothered that my hair was long or my clothes were a bit ragged (my having two older brothers filled out my wardrobe to a degree).

At least not that I noticed.

I stopped going to Temple Israel when Rabbi Weinstein (still battling my Mother about family dues) refused to let me change my 3rd grade Sunday School teacher from Mrs. Whitman (a teacher who seemed pleased at the thought of having a fourth Scudder child in her classroom, and not in a good way) to Mr. Hoffman. Instead, I joined a bowling league where many of my friends bowled and I was seamlessly welcomed onto two different teams.

In fact it was so seamless that my parents did not know for about four weeks that when I was leaving home to walk to Temple I was actually going to the bowling alley. When they learned of my protest I was supported, not admonished.

No, all in all I had little to complain about during the elementary years. They were years of fun and exploration and learning and socializing, much like when I took the Basic Collaborative Training and that initial excitement of finding something I loved and to which I was drawn. From my early years I still carry faith and optimism in each collaborative case that we can “have each other’s backs” even in the course of a divorce.

Junior high school (7th through 9th grade) became more problematic. I had to deal with that “Scudder-thing” again, something about being the fourth Scudder to come through the school. My siblings must have left a fine legacy because on my first day at the school I was pulled out of an all-school assembly (I was sitting in the middle of a row so my public shaming was staged and complete), marched to the Principal’s office and sent home for being inappropriately dressed. I was told that I had to walk home and tell my Mother I was sent home because of my clothes, put on pants with no holes in the knees and a shirt that was my size, not my brother’s. Only then could my Mother drive me back.

He did not tell me to cut my hair.

In Junior High my hair got longer, I continued to excel in school, got placed on the “smart kid” track, and I joined different school sports teams on which my friends were also playing.

But things were changing. Friendship, and the idea of what constituted friendship was changing. We were not children anymore, acting upon our childhood enthusiasm, spontaneity, and carefree attitudes. No, in Junior High School we started to exhibit the roots of our own upbringing, what we were learning in our own households.

Not only did invitations start to become fewer, and unlike the pulling of hair, name-calling and occasional punch that was my elementary school experience, the actions of my friends took on a different tone. Now I would call and ask what was up and make plans to meet, and nobody would be there when I arrived. Perhaps more shaming, one of my friends would call and say he would pick me up at a certain time; only to never show up.

It took me awhile to get the message, but eventually I moved on to a group that accepted me for who I was and welcomed me into their embrace, the Omaha Jewish Community of B’Nai B’rith.

It was with this group that I learned about friendship at a different level. These people had my back in a way I needed at that time, and I had theirs’. The best man at my wedding comes from this group, as do others who have an open door to me if my travels take me to their city, as my door is open to them.

This intentional act on my part to choose something nurturing had future, unintended consequences.

My relationship with the Jewish group had to be a weekend relationship as only a handful of my Jewish friends, and only one from AZA #1, the Jewish youth group I joined, attended my school. And none lived near me. So I traveled to and from school on my own, did my homework on my own, and only on weekends socialized with my friends.

I tried to live a high school life that worked for me and which I thought was normal. Despite the fact I was one of the best athletes in the Jewish youth group leagues, the high school coaches for both basketball and baseball cut me at the first opportunity. Of course my hair was a bit longer than it was in Junior High School, but it felt more to me like I was different, an enigma, a problem and that nobody wanted something so different around.

So I withdrew even more from the high school social scene and relied more on my Jewish friends.

At age 17 I went back to Temple Israel with my friend David Merritt, and asked Rabbi Weinstein if we could be Bar Mitzvah’d at the Temple. Both David and I had not understood at age 13 the importance of this rite of passage. At age 17, both of us having found support in the Jewish community when our other community failed to meet our needs, we found it an important ritual.

Rabbi Weinstein appeared supportive, and told us to go learn Hebrew and come back to talk more. So David and I hired the Hebrew instructor at Temple Israel. She was very excited about teaching us and being part of this event. In 1977 Omaha, NE nobody had gone back at our age to be Bar Mitzvah’d.

At the second meeting she told us that she was not allowed to meet with us anymore. She said that Rabbi Weinstein would not allow her to work with us. That “Scudder-thing” again, I suppose.

So David and I went to Miles Riemer, the father of a friend of ours, who said he was honored to teach us Hebrew and help us with our torah and haftorah portions. When we were done we went back to Rabbi Weinstein, who must have had a talk with Rabbi Brooks, the previous head Rabbi at Temple Israel and had know our family since they started attending Temple Israel.

We were welcomed back and David and I were Bar Mitzvah’d on the same weekend. It was a joyous event, one that I will never forget.

Shortly after my Bar Mitzvah I graduated High School. Early. Before the rest of my graduating class. I did so by taking summer school English. Incredibly, even by graduating I could not stop the torment of my Senior year.

As I loved basketball but had not played on the school teams, I played intramural basketball on a team with a couple of Jewish friends at the school. The intramural season extended after my December “technical” graduation. During one of the games the gym teacher stopped our game, walked on to the court and asked me to leave. When I asked the reason I was told that it was brought to his attention that I was no longer a student at the school and not eligible to play intramural basketball.

In January 1978 I attended a basketball game between my apparently former high school and a rival high school. Again, my love of basketball. As the game went on the gym was turning into a powder keg of emotion. Fights broke out at halftime, calmed down, and then exploded again as the two streams of supporters met in the hallway outside the gym after the game. The fighting stretched out into the parking lot. Being a “Peace, Not War” guy and not being interested in fighting for the “honor” of my school I floated to the edge of the parking lot, away from the school and the chaos.

It seemed safe out there. Madness all around but safe where I was.

Until I saw something that, in my mind, really left me no option.

What I saw was a boy on his hands and knees. And four or five other boys kicking and punching and just going off on him. I did not know the boy on the ground. He could have been from our high school or the other high school. It did not really matter to me. I ran across the parking lot and threw myself into the fray, knocking as many people away from the boy as I could.

I do not know how it worked out for the boy. For me, I ended up with my arms held behind by back and waking up the next day in the hospital with a concussion and lacerated face from someone kicking my face into the ground after I had been knocked out.

Surely this was enough for one person to have gone through Perhaps I could just make it to graduation. Maybe not.

Later that Spring, after physically healing but not really healing, I was ready to graduate. I was invited to sit with my class of 864 and their families in the Civic Auditorium, walk across the stage, get my diploma and shake the hand of the Principal telling me what a pleasure it was for him to have me in his school.

One of the pre-graduation events was a softball game. I went to that event hoping to have fun and reconnect with my class.

What I connected with was the softball, sending it far over the left fielder’s head for a home run. Between innings the left fielder, a childhood friend, came up to me and called me a “dirty Jew.”

Stunned, to say the least; and then a light bulb went on for me. A realization that the years of abuse and disconnect and being ostracized was due, perhaps in large part, to that simple fact.

For me high school was not a pleasant time. By the time I graduated I was going to get out of town, I was going to spiritually die, or I was going to hurt myself. It was only the acceptance letter that I received from Hampshire College in Amherst, MA that allowed me to see a path out of my situation.

I left Omaha with a suitcase full of experiences and lessons from which I continue to learn and grow. My experiences there with prejudice, shifting social circles, and not having the tools to be able to express myself or recognize certain behavior in myself or others left me with lots of work to do. I continue to do that work to this day.

FRIENDS, Part 2 of 2:

At the 25th high school reunion I learned that during high school several of my classmates experienced me as an enigma. I was not surprised by the description, only impressed that someone put it into such succinct words. That word alone, however, does not adequately describe my experience growing up in Omaha.

It is not as if I did not return to Omaha for twenty-five years after graduating from high school. I came back to visit my family, to attend memorial services for my Grandmother, Mother, and for my Grandfather’s 98th, and last, birthday. My friends, however, did not live in Omaha. They were in Los Angeles, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Minnesota and the other places they moved to after leaving Omaha.

As for my friend at the softball game, he continued to stay in contact with me. He initiated all of the contacts. He invited me to his wedding. He called me on occasion, updating me on his life. He made a point of telling me that some of his best friends were Jewish and that he was active in the Jewish community in Omaha.

Finally, after one of these phone calls it came to me: he did not remember the event that so dramatically shaped my life.

When he next called me to check in to tell me the goings on in Omaha I said, “You don’t remember, do you.” He said “remember what”, and I told him my story of what happened and how it impacted me. He quietly listened. When I was done I could tell he was shaken. He talked for awhile then, saying he could not believe that he could have said such a thing, that he did not consider himself anti-Semitic though he said that a couple of other friends we hung out with were and, that if it happened, he was truly sorry.

My guess is that this was twenty years after I left Omaha. Over the next five years we stayed in contact, with him contacting me, and me contacting him.

Then came the 25th reunion. By this time I felt okay about going back home into the “friend” scene. For support I enlisted the help of my Jewish friend from Los Angeles, whose parents still lived in Omaha so that if things got strange we could hang out with each other.

It was quite an extraordinary experience. My friend from the softball game was there and we hung out together on several occasions with other people. With each group he did something that swelled my heart and brought tears to my eyes: he told our story, unabridged and uncensored, making his amends in public.

He had my back and I had his. We had overcome a traumatic event that had rent our friendship for over 25 years.

Friends.

How many times have you seen this happen in one of your Collaborative cases? It is an incredible thing to see and feel.

FAMILY, Part 2 of 2:

On July 2, 2013 at 9:52 a.m., on the weekend of my 35th high school reunion I was having coffee with the friend with whom we had repaired our relationship and another mutual friend from our elementary school years. My phone rang and the i.d. indicated my Father was calling. When I answered the phone it was not my Father at all, but an Omaha police officer saying that my Father had collapsed in a parking lot, that he was receiving CPR, that he had been unresponsive for ten minutes, was not expected to live, and that I should meet them at Methodist Hospital.

My friends offered to drive me to the hospital. I declined, needing the time to gather my own thoughts. Who do I call? What do I do? What awaits me at the hospital? Was yesterday the last time I would ever talk to my Father? With my Father’s death that was one less person in the generation of my family that preceded me. Good questions; not a lot of answers.

On the drive to the hospital I called my sister. Of the six children she lives the closest to my Father, in Lincoln, NE, and is his Power of Attorney for medical decisions. Given that my Father had been scheduled for an aortic valve replacement and double bypass on July 11, 2013 she had been regularly attending his doctors appointments and was current on his medical condition.

Except that he did not make it to his surgery date. I thought she would be a little disappointed that all the hard work she did in supporting Dad might be for naught.

She was. When I reached her she was on duty and had to find someone to come in to replace her. As the managing nurse on duty she could not just leave.

So I had the ER hospital shift to myself. They put me in a chair in the hallway. They updated me on my Father’s progress; he was still unresponsive, going on fifty minutes. The police officer who called gave me the clothes that my Father had been wearing, expressed his surprise my Father was still alive and shared hope for his recovery. The on-duty Clergy came by and offered me support. When asked, he said that the Rabbi had Monday’s duty and it was Sunday. I smiled a bit.

The ER nurse on duty came to tell me that my Father was still unresponsive and that they were going to chill his body to prevent tissue damage. I asked if I could see him before they took him and they escorted me back to the room where he as lying on one of those long, metal tables with sheets and tubes and medical equipment all over the place. I started talking to the doctor about what they were going to do next and then, I like to think that maybe it was his hearing my voice, my Father lifted both arms in tandem from the elbow and put them back on the table. I looked at the doctor who, when I asked, could not tell me if the movement was voluntary or involuntary. I then went to my Father’s side, grabbed his left hand, and talked to him. Even though he could not open his eyes he clenched my hand and turned his head toward me.

Perhaps the most wonderful, scary, magical, fabulous thing I have ever seen in my lifetime.

I looked at the doctor, who said “change of plans”, and they whisked my Father up to ICU.

More waiting. My sister finally arrived. I was glad because I felt out of my league, not knowing the medical “lingo”, what it meant or what questions to ask that would get me helpful information. I was glad because I had someone I trusted and loved to be with. Someone who I could work with, who had my back, as I had hers.

The rest of that day there was little we could do at the hospital. They stabilized my Father and put him in a coma. He was in good hands so my sister and I went to my Father’s apartment where we cleaned his refrigerator, washed the sheets on his bed and towels in the bathroom, and started going through his papers to find information on who we had to contact.

My Father’s communities. His AA groups. The people he sponsored. His Big Brother’s family (we told them my Father would not be at next week’s celebration). The Omaha Folklore Society. The Shape Note Singing group. The Saturday morning bowling team. The Monday morning bowling team. The Thursday bowling team. The book club at the library. The pharmacist at Walgreen’s. My Father had a folder for pretty much every community in which he participates.

To each we placed a phone call and asked their help in letting others know about the situation. It was a lovely and heart-wrenching process.

When I arrived at the hospital the next morning, to my pleasure my Father was conscious and his eyes open, albeit with a breathing tube so he could not talk. He tried to communicate nonverbally to us but had little success, until my sister went back to the apartment to get his IPad. We had to hold it for him as he typed and it took awhile for him to get coordination back to type legibly, but eventually came the first word:

barbecue

Very funny, Dad.

He had eight rib fractures from the CPR. He hurt. He was scared. He did not know what happened. We told him later that day that it just so happened that the first responders were shopping for groceries for their station house at the supermarket where he collapsed, meaning that very little time passed between his collapse and the starting of CPR (nationally only 10% of CPR patients survive). We told Dad that we had taken big boxes of Russell Stover chocolates to each of the two station houses that responded with cards saying thank you. He typed: “Not my chocolate?” We assured him his stash of chocolate at his house was safe.

Very funny, Dad.

I extended my stay in Omaha for 24 hours so that I could be with my Father and sister until he was taken in for his heart surgery. By the time I boarded my plane he had been in the operating room for five of the nearly nine hours of surgery he underwent. I could not help but spend much of the flight, thinking about all that had transpired on this journey.

My trip to Omaha.

Going Home.

CONCLUSION:

My Father survived this incident. He had open-heart surgery on July 4, 2013, was in the hospital for a month and then a rehab facility for another month. He returned to his home on September 12, 2013. He faces a long road and he will not be driving any time soon. He has his sights set on Spring 2014.

Trauma. I wonder how I will respond when a client or a fellow practitioner tells their story of collapsing in a parking lot, or having a friend or relative do so. In Omaha I learned that trauma can be survived, even if severe. All collaborative practitioners, in doing this work, at some point will be called on to stand in the midst of trauma in order to help our clients, their children, and their community. By working through the trauma we can help them emerge in a new, stronger form.

I learned a lot on this trip home and I have tried to share some of what I have learned in this series of three articles. Here are the things that stand out most for me:

· When we are young we act authentically. As we grow older we become more guarded and act with less authenticity. We become more concerned about how we are perceived, what people will think, and our fear of failing and looking foolish doing so. Authenticity is something that has to be chosen daily, and often several times a day. Choosing authenticity requires courage as in making this choice we let go our concern about others judging us. In order to be a quality collaborative practitioner we have to reintroduce authenticity into our lives, not only in our collaborative work, but in our daily interactions with others as well. As we reintroduce authenticity back into our lives on a more regular basis we reduce the likelihood that it will be lost again.

· We will have better results if we focus on the little things rather than the end result. The reward is in doing the little things well and letting the result take care of itself. Most people may be uncomfortable with this approach to a goal so it is incumbent on us to be consistent, grounded, and transparent. How much more different from litigation can we get by letting go of the result, letting go of winning, and committing ourselves to trusting our clients and the professional team to create a result that reflects what the clients determine is fair and just?

· There is a power in making amends. An authentically made apology has the potential to transform entire communities, not just individuals. An authentic apology, when expressed and received, will bring tears to the eyes of the people involved and will create change that will last a lifetime. These types of moments are not planned for. They are not a “goal” of any collaborative case. They just happen, but only when the professionals have managed the case in such a way creates the conditions necessary for such an event to happen.

· We will be better at what we do, in any walk of life, if we reach out to communities outside our geographic areas. By doing so we share and learn from experiences that are not available or common in the limited area where we live and work.

. There is power in Community. Communities are places of support, empathy, compassion, creativity, entertainment, education, expression, celebration, shared values and morals, and mourning. As we do the work that we do the better we understand the communities from which our clients and fellow practitioners come the better we will be able to meet and even exceed their needs and expectations.

Our clients are on a journey that intersects for a limited period of time with ours. We are best served, and we serve best, if:

· We commit ourselves to the little things that escaped notice before we made our commitment to collaborative excellence;

· We expand our learning opportunities by entering into dialogue with communities outside our localized groups;

· We create a container that is welcoming of all the communities that our clients and fellow practitioners bring to the work that we do, as these communities are the essence of who we are and how we walk in the world; and,

· We embrace our roots, the roots of our clients, and the roots of the professionals with whom we work. By doing so we create a collective wisdom that that will provide benefits for years and generations to come

Now you have read my story.

Consider that each of our clients has their own story, and each professional on all of our collaborative teams have theirs.

And you have your story, too. Take the time now to look at the paper that you started with as you began reading. What list of values have you come up with that are important to you? What events in your life have you noted as playing an integral part of who you are?

We all have our stories. We need to embrace these stories so that we can help our clients with theirs.

This is essential to the collaborative work that we do.

***********

Join this discussion by clicking here!

You’ll have to sign in with your twitter account or your email address.

* The author acknowledges and expresses gratitude to Gloria Kay Vanderhorst for her editorial comments on this article and to Gloria and carl Michael Rossi for establishing the World of Collaborative Practice as a meeting place for topics related to Collaborative Practice.

Share your thoughts here and in your network.